Issue 15a / 26 April 2024

In part one of this week's spoonful of electronic goodness... Book Of The Week: ‘Dream Machines – Electronic Music In Britain From Doctor Who To Acid House’ + interview with the author Matthew Collin

Oh hello. Last week’s two-part mailout was a surprising success so I’m doing it again. They’ll be two mailouts today, this one (9.30am), which will be the Album Of The Week and interview, and one at 3.30pm that’ll be full of new releases, including Track Of The Week, along with books, events, gadgets and the like.

And talking of books, this week there is an actual Book Of The Week instead of Album Of The Week. Do the experiments never stop? There’s so many great books coming out and they deserve the same sort of treatment we give to albums. So every now and again there will be a Book Of The Week. I’d love to do both, but there are, currently, only 24 hours in a day. If that changes I can certainly write some more.

I hope you don’t mind hearing the whirrings of my mind as I figure all this out. I’ve got to tell someone and who better than people who read all this. I’d be keen to hear what you think about it all. Feel free to drop me a line or strike up a chat in the comments. I’ll see you all back here at 3.30pm. Don’t be late.

Neil Mason, editor

moonbuildingmag@gmail.com

Issue 14 Playlist: See this afternoon’s mailout

Buy us a pint: ko-fi.com/moonbuilding

***ADVERTISE HERE***

Email moonbuildingmag@gmail.com

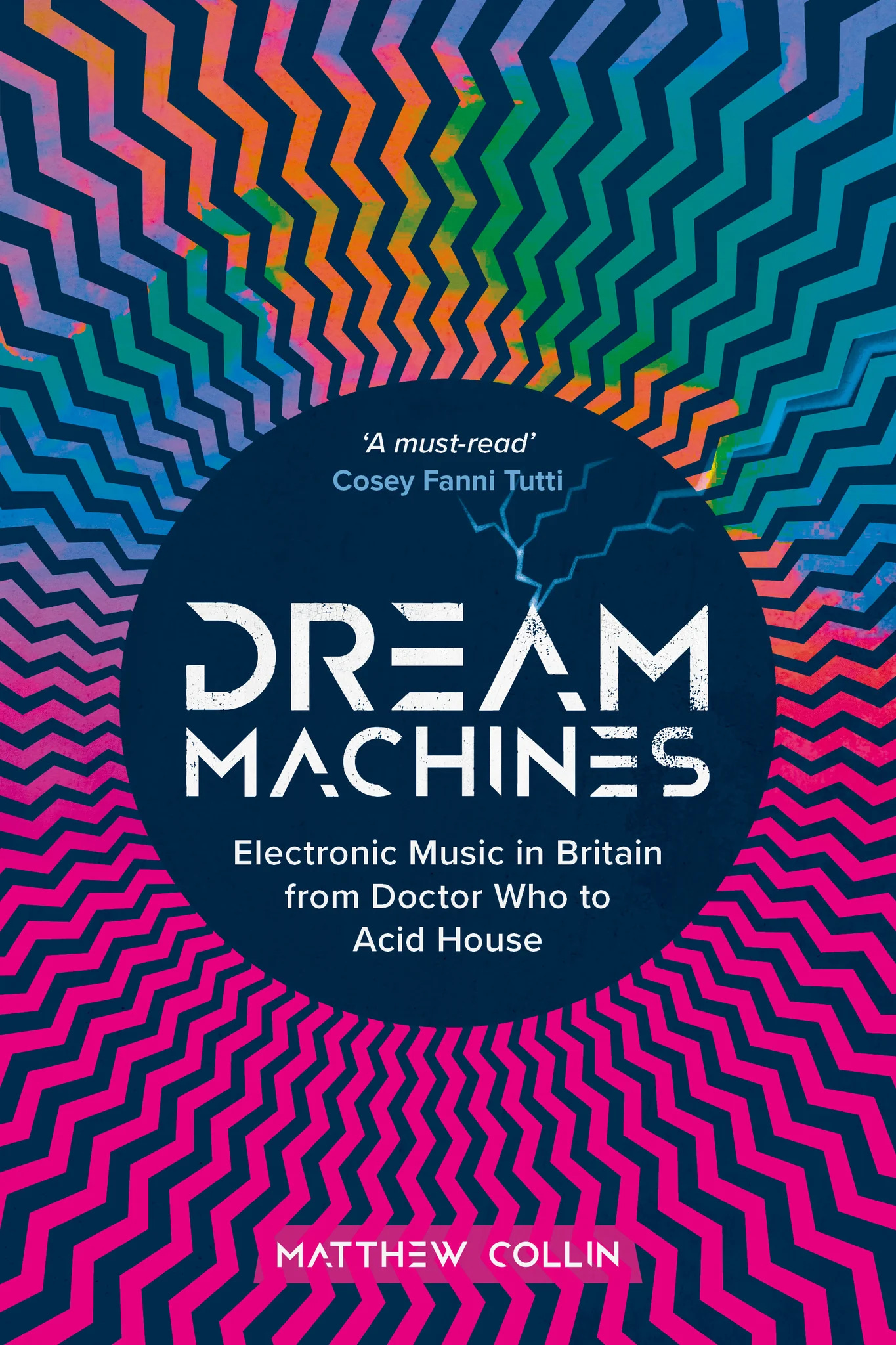

MATTHEW COLLIN ‘Dream Machines – Electronic Music In Britain From Doctor Who To Acid House’ (Omnibus)

You’d be forgiven for thinking that there’s a lot of this kind of thing about, bookwise. Only last week I mentioned the paperback of Richard Evans’ ‘Listening To The Music The Machines Make – Inventing Electronic Pop 1978-1983’. And on the day ‘Dream Machines’, the latest book from the author of ‘Altered State’ and ‘Rave On’, was published, Simon Reynolds let rip with ‘Futuromania’, his first book in eight years, which is also a history of kinds. Two books by writers of this quality on the same day, in the same ballpark, is not only a huge treat, it’s a sign of the times. Electronic music is very much on the agenda.

In ‘Dream Machines’, Matthew Collin focuses on the electronic music coming out of Britain and sets himself some perimeters. The story starts with the Second World War and EMS VCS-3 co-inventor Tristram Cary joining the armed forces in 1943 and finishes with the illegal raves staged in and around London’s M25 in 1989 and Orbital, the band whose name they inspired.

The story of British electronic music is unique. Across mainland Europe in the early 1950s, national broadcasters were establishing electronic music studios with the likes of Pierres Schaeffer and Henry working in Paris, Karlheinz Stockhausen in Cologne and Luciano Berio in Milan, but there was nothing in the UK. While working as a studio engineer at the BBC, Daphne Oram began lobbying for such a facility. She contributed to a report for the BBC’s Head Of Programme Operations in November 1956 that laid out their plan, including staffing, equipment and, most importantly, output. Whereas the European outlets saw their creations as art, the BBC unit would be used to “create unusual sounds for radio dramas and productions for the features department”. The BBC Radiophonic Workshop was born and electronic music wouldn’t be same again.

The fascinating part of all this is that the generations of children who grew up with the sounds of the Workshop didn’t know that’s what it was. The work was transmitted as part of schools TV and radio as well as for BBC TV shows so it just seeped in as we watched and listened, every single day. The influence of the ‘Doctor Who’ theme tune alone is enormous. Little wonder the UK is awash with such a rich electronic music heritage.

‘Dream Machines’ is meticulously researched and beautifully crafted as you’d expect from a journalist of Matthew’s calibre and comes arranged in neat chunks by chapter and then by sub-section. So Chapter 1 is “Journey Into Space – Musique Concrète And Radiophonic Sound” and the sub-sections cover off Daphne Oram, Tristram Cary, The Radiophonic Workshop, Janet Beat, FC Judd, Desmond Leslie and Delia Derbyshire. You already want to read all that don’t you? And so it goes on, page after page, covering off space-age pop and psychedelia, prog, industrial, synthpop, art rock, dub reggae, electro and hip hop, samplemania, house, techno and acid and much more.

Just skimming the contents makes you want to jump in, when you do finally get stuck in, it makes your head spin. The stories pour off the pages. What is surprising when you lay out a history like this is the clarity with which you can see how everything is connected. Steve Hillage is connected to The Orb, Bronski Beat to Joe Meek, Mad Professor to FC Judd, Kate Bush to David Vorhaus. It’s like a huge dot-to-dot, with much of it, it has to be said, leading back the Workshop.

There’s more than a couple of moments that really struck me. Firstly, you’d think that the trailblazers would have been the big guns, those operating at the top of the tree in the 1960s – The Stones, The Who, Floyd, The Beatles, but no. Floyd played their part, but it’s hard to tell if they were truly breaking new ground or just taking a shitload of drugs. The Stones and The Who, well, they played almost no part. The Beatles, of course, created a seismic shock in the shape of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’.

There’s several acts that do leap out as being hugely influential. One is Hawkwind whose influence was spread far and wide by their endless gigging, playing shows and handing out free LSD seemingly everywhere. Their cosmic space rock sound was enhanced by their roadie, DikMik, who performed with the band making wild noises using an electronic signal generator, an echo unit, fuzzbox and wah-wah pedal. When Del Dettmar, a second roadie, joined him with a VCS-3 in 1971, their sound travelled even further into the stars. With their relentless touring, Hawkwind left an impression on those in the audiences who went on to form bands of their own, among them New Order’s Stephen Morris. “When I saw them live,” he tells Matthew, “I got a full sonic psychedelic onslaught that was kind of punk before punk. It was great the way that they were using synths, but not with a keyboard, just as noises.”

Gong, whose frontman Daevid Allen learned the art of the tape loop from Terry Riley no less, were surprisingly influential. It’s also surprising the impact Malcolm McLaren’s ‘Buffalo Girls’ had in particular, and more broadly, how important electro was. I loved the Street Sounds compilations (there’s a great story about ‘Street Sounds Electro UK’ that I won’t spoil), but I don’t think I realised quite how big, or how far reaching, electro was as a genre.

Again, I loved Manchester electro outfit Quando Quango and their influence was considerable. Consisting of Mike Pickering and Hillegonda Rietveld and produced by ACR’s Don Johnson and New Order’s Bernard Sumner, their music really hit home with NYC DJs like Larry Levan and Mark Kamins. They were not only exporting electro back to the streets it came from, but years later Hillegonda was researching her PHD about house music in Chicago and discovered her band had influenced Vince Lawrence, who recorded ‘On And On’, one of the very first house records.

I’ve only just grazed the tip of this book’s iceberg of knowledge. There’s so many rich stories that all play their part in what is, when you see it laid out like this, an incredible tale. Best of all, it is all connected.

At the very end comes Orbital, rave icons who grew up with the ‘Doctor Who’ theme tune ringing in their impressionable ears. In 2017 they found themselves on stage at the Blue Dot festival in Cheshire along with original members of the Radiophonic Workshop performing, you’ve guessed it, the ‘Doctor Who’ theme. The whole thing comes full circle. It’s the perfect ending for the book, making its point perfectly. [NM]

‘Dream Machines – Electronic Music In Britain From Doctor Who To Acid House’ is published by Omnibus and is out now. Find it at the Moonbuilding bookshop.

See below for a bumper playlist compiled by the author…

MATTHEW COLLIN

With a Beatles jump-start, a leg up from Hawkwind, a ‘Top Of The Pops’ following wind and a good dose of dub reggae, we catch up with the esteemed author for a freewheeling chat about his new book ‘Dream Machines’, which lifts the lid on the

rich history of electronic music in UK

Interview: Neil Mason

Photo: Nia Gvatua

The book is an excellent read, but the early years chapters are especially captivating, why do you think that is?

“There’s something very attractive about those early years of British electronic music because there’s an innocence and an energy and a feeling of exploring new horizons that is maybe absent from contemporary electronic music, because that’s obviously built upon all this work from the past. So to spend some time in this quite innocent, naive, but at the same time, incredibly creative period, was very attractive.”

It’s all very well researched, very thorough…

“Well, it was a lockdown project. We had a lot of time didn’t we?”

Would you like to set up the book for us?

“‘Dream Machines’ starts around the time of the Second World War and my idea is the war was really important to the development of electronic music in Britain. People went off to war, and maybe they’d served in signals or radar, and they came back with new skills in electronics. They’d then start to acquire ex-military equipment, which they used to create their own sound studios. Just after the war you also got the first commercially available tape recorders that allowed people to actually manipulate sound. You could run it backwards, slow it down, speed it up, chop it up and create a different narrative. Sound became something that was malleable and could be manipulated. It no longer had to be linear.”

The other thing that changed was the role of women in the workplace…

“Because the men were called up, their jobs back at home were undertaken by women. At the BBC they recruited several hundred women to work in positions that the men had vacated to go and fight. And some of those were technical positions.”

Which is where Daphne Oram comes in. She was key in setting up the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, an institution you can’t understate the importance of

“For people of my generation, born in the 60s, we grew up with the music or soundtracks of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop all around us. We didn’t really think, ‘Oh, this is electronic music and I like it’, you just kind of soaked it up by osmosis. It was just part of the ambience of everyday life.”

With the BBC at the time, the Workshop was never going to be like the electronic sound studios that were in Europe was it?

“Yeah, I mean I’ve worked at the BBC and it has a very functional idea of what it’s doing. It doesn’t see itself as an incubator for avant-garde art, never has done, and this is what Daphne Oram came up against once they set up the Radiophonic Workshop. It was set it up for purpose, to make sounds that would soundtrack drama programmes.”

It’s remarkable that the BBC agreed to it really isn’t it?

“Before the Workshop, the BBC was very much against the production of electronic music. It was seen as a pernicious foreign influence. They were worried the French or the German influence would contaminate our British musical culture. It seems ridiculous now that this could ever have happened, in a country where we’re totally pro-European!”

So Europe had all this state-sponsored avant-garde sound art and we had the ‘Doctor Who’ theme?

“We had the ‘Doctor Who’ theme. And it was transmitted to the public, not as high culture music in concert halls, but on the telly for kids. There is this theory that’s why Britain was so dominant in electronic pop, especially in the 80s and 90s.”

Because sat in front of the television watching all this was a whole generation who grew up to be the musicians we know today?

“If you were a kid, you watched ‘Doctor Who’ that was just the way it was, so therefore you got exposed to it. Same if you had to listen to schools radio, it wasn’t a choice you made, it was your life at the time. You didn’t think about it, it was part of your musical education without even realising you were getting a musical education.”

And this message was amplified by The Beatles who contribution to all this was ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’?

“The Beatles were very important for British electronic music, but not necessarily in terms of the music, the output. There’s this period in the mid-60s when they started looking around for something else, they were looking into Eastern spirituality, avant-garde art, black American music, free jazz. And electronic music was one of those esoteric things they picked up on and refracted into pop culture.”

It’s hard to get across how important anything The Beatles did was to the rest of the musical community and society at large. Their influence was vast wasn’t it?

“I’m not saying the experimental side of what they did was any good, but they brought it into the pop vocabulary. There’s the one great track, ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’. It’s an absolutely brilliant record that combines all that Eastern spirituality, psychedelic drugs, tape loops, backwards guitars, it’s got it all. Everything boils down into this one track and then, like a bomb, the whole thing just explodes.”

You’d expect the big guns at the time to wield the most influence, but aside from ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, there’s very little from the other big groups

“Have you heard Mick Jagger’s synth work? He did the soundtrack for an art film by Kenneth Anger in 1969 called ‘Invocation Of My Demon Brother’, which I describe in the book like a remote control car trying to do a three-point turn.”

One of the other aspects you can’t underestimate is the importance and influence of was ‘Top Of The Pops’…

“It’s amazing that now ‘Top Of The Pops’ means absolutely nothing, in fact, linear terrestrial TV means very little these days in terms of influence because people just aren’t watching it anymore. A lot of the media I talk about in the book has gone. The role the BBC had when there were no other channels... the music press used to have a major role on public discourse. But ‘Top of the Pops’…”

You didn’t miss it

“You couldn’t miss it.”

Roxy Music’s appearance in 1972 caused an earthquake didn’t it?

“They were the first band to have someone who wasn’t playing an instrument, he was playing some kind of box. The fact that he was dressed up in feathers and furs and make-up and he was balding, but he had long hair and looks like quite the character obviously added to the whole thing. There wasn’t such a thing as a synthesiser player. It was something that was invented by people liked by Brian Eno in Roxy Music.”

And the box was an EMS VCS-3...

“Which is another connection, going back to the war. One of the first composers of musique concrète in Britain was Tristram Carey, who worked on the invention of the VCS-3. So it all connects back. Tristram Cary thought the VCS-3 would be used for educational purposes or maybe some classical composers might use it. He didn’t envisage that it might be used in rock or pop music. So Brian Eno, processing the sounds from his band through his VCS-3, invents this role of the synthesiser player.”

The way the book is structured, through its series of very well researched deep dives, makes you realise that some artist aren’t perhaps as influential as you thought. One of them being The Human League

“Do you think so? For me The Human League were really important. There weren’t dance music clubs when I was growing up in Nottingham in the same way as there are now. You used to go to a club and they’d play like maybe 15-20 minutes of electronic music, then they’d play 15-20 minutes of Motown, then they’d play 15-20 minutes of pop.”

Which made for an interesting crowd

“I think The Human League represented that coming together of the Saturday night out-on-the-town hedonism and the arty stuff, which is what I was. Part townie, part arty. I loved the mixture of those two cultures and I thought that was a really British thing. Those Human League songs are like hymns to a working class Saturday night aren’t they? And that was why it was so successful because it spoke in that way to so many people.”

Do you think perhaps their influence wasn’t so much the music as the aspiration? The lifestyle?

“I think their influence was making great records. I think what gave ‘Dare’ that charm is not only the amazing production of Martin Rushent, but it was that the girls’ vocals were ever so slightly unprofessional and that was the pop dream wasn’t it? It was like going into your hero’s movie kind of thing, becoming part of this glamorous world of pop. And for the audience they hear themselves reflected within it, and I think that’s why The Human League were so attractive… although I had bought the previous records because I was a bit of an arty idiot.”

While the book is about British electronic music, nothing exists in a vacuum does it? All this stuff was touched by music coming from all over the place

“Yeah, I mean obviously there had to be some limits to the project. The focus is on Britain from the 1940s to the end of the 1980s, so it couldn’t be an everything everywhere kind of thing, but there isn’t really such a thing as pure British electronic music, there can’t be. Any kind of music is a series of cross-continental conversations. Things like electro or hip hop had a massive influence on the music that was made in Britain. People like the minimalist composer Terry Riley was massively significant. And then there’s Kraftwerk. And of course it’s also a conversation between people and technology and a lot of that technology was Japanese.”

There is a very illuminating chapter on the huge influence of dub reggae and sound systems

“A massively important thing for not only electronic music, but Britain in general has been the influence of Jamaica. It’s been massive on British culture.”

You talk to Neil Fraser, The Mad Professor, and he says he was building his own equipment using diagrams from FC Judd’s Practical Electronics magazine, which is pretty amazing. Another line connecting back to those early pioneers…

“I also interviewed Dennis Bovell, who was one of the first dub producers in Britain, and he said the ideas of dub have changed the way we listen to music, the way we conceive music and the way we execute music. We listen to music in a different way because we're listening in terms of the space between things. Brian Eno talked about this in the late 70s, he was talking about dub music being much more influential on him than anything Stockhausen or Berio or any of those guys ever did. It was more useful in terms of making popular music.”

The book ends with Orbital who are the essence of everything you’ve talked about, the perfect encapsulation of everything from the Workshop right through the modern day

“They grew up on the Radiophonic Workshop and later collaborated with the surviving members of the Workshop at the Blue Dot festival.”

Which is quite a crossing of the streams?

“Orbital are also part of that do it yourself tradition. Initially they were recording on secondhand equipment in their parent’s house in a cupboard under the stairs. Paul Hartnoll, who I interviewed for the book, was saying that the major expense of making the first version of ‘Chime’, a track that made their reputation and became an international hit, was that he had to master it onto a metal cassette, which they had to spend £3.50 on.”

He wondered if it was worth the money and almost didn’t bother!

“He told me he thought the tape seemed really expensive and was really unsure about having to invest in it! So this was the DIY tradition going back to post-World War Two with people buying their secondhand oscillators from military surplus and you can see the line going back to this from Orbital. One of the really rewarding parts of writing the book was when you can feel these connections and you feel that it’s all part of the continuum.”

Did you know that’s where the book was going to end? Or was it like a lightbulb moment, because it’s perfect!

“It was a kind of a lightbulb moment, an ‘oh thank you’ thing.”

For more, follow Matthew Collin on Instagram

***ADVERTISE WITH US***

Big ad, little ad, cardboard box - email moonbuildingmag@gmail.com

A MESSAGE FROM THE MOTHERSHIP

SPRING SALE…WHILE STOCKS LAST…SPRING SALE…WHILE STOCKS LAST…

MOONBUILDING ISSUE 4, WAS £10 NOW £5 (+P&P). GRAB YOURS WHILE STOCKS LAST … MOONBUILDING.BANDCAMP.COM

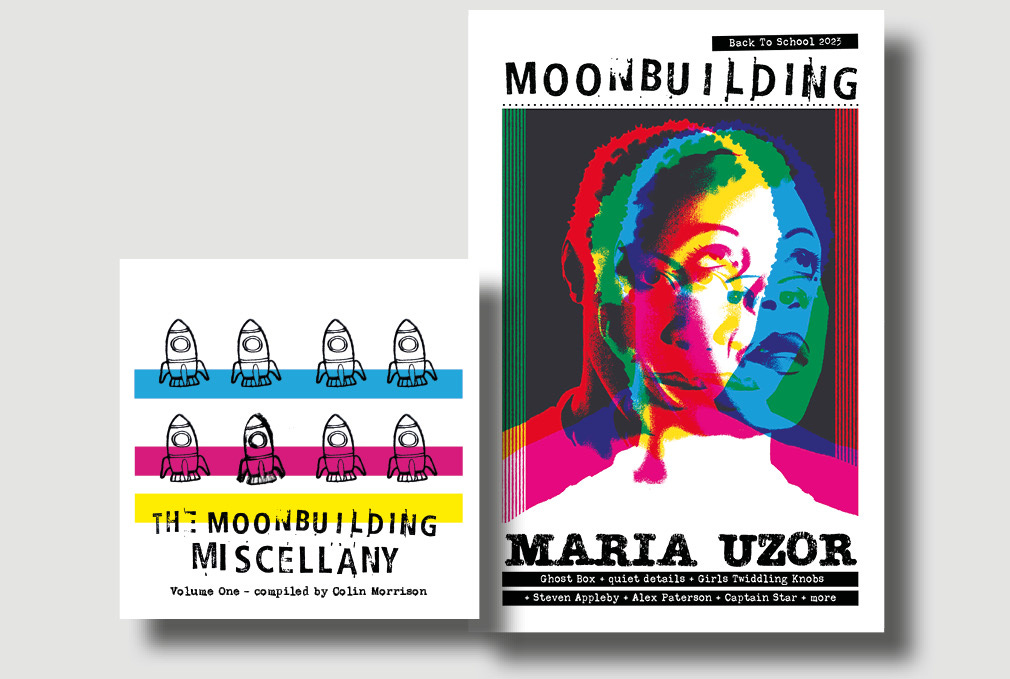

The current issue of MOONBUILDING is full to the gills with the good stuff. On the cover, star-in-the-making Maria Uzor, we profile label-of-the-moment quiet details, there’s an incredible interview with Captain Star creator Steven Appleby, and Ghost Box’s Jim Jupp gets busy with our There’s A First Time For Everything questions.

We review a big pile of releases from labels including Castles In Space, Woodford Halse, Persistence Of Sound, Assai, Ahora, DiN, Werra Foxma, Ghost Box and many more. There’s a column from The Orb’s Alex Paterson and the world-famous Captain Star cartoon strip.

This issue’s CD is ‘The Moonbuilding Miscellany – Volume One’, which is put together by CiS supremo Colin Morrison. It’s a belter featuring tracks from the likes of Lo Five, Lone Bison, Twilight Sequence, Ojn, NCHX and more.

Moonbuilding Weekly is a Castles In Space publication.

Copyright © 2024 Moonbuilding

Brilliant stuff and a cracking interview, will be ordering the book today!