Issue 29a / 2 August 2024

Your essential DIY electronic music bulletin... Bumper Book Of The Week issue starring Justin Patrick Moore's 'The Radio Phonics Laboratory'...

It’s been quite a week for the new issue of Moonbuilding. We gatecrashed the Bandcamp Discover bestseller chart on our first weekend on sale, which was great. Thanks to everyone who bought a copy and a big hello to all the new newsletter subscribers.

So this is a Book Of The Week special issue featuring ‘The Radio Phonics Laboratory’, a wonderful new volume by Justin Patrick Moore. There’s an interview with Justin in the new issue of Moonbuilding (have we mentioned there’s a new issue?), but here we publish the whole chat, from start to finish. It’s lengthy, but it does such a good job of telling his tale we thought it’d be a shame if it didn’t find its way into the world uncut.

We’ll be back this afternoon with our usual Track Of The Day and Good Stuff recommendations, handpicked from the latest new releases. I’d say there’ll be no more mentions of the new issue of Moonbuilding today, but I know that’s highly unlikely. I’ll shush once it’s sold out.

Neil Mason, editor

moonbuildingmag@gmail.com

Issue 29 Playlist: See this afternoon’s mailout

The Moonbuilding tip jar: ko-fi.com/moonbuilding

*** This newsletter is sponsored by DiN Records – for more, visit dinrecords.bandcamp.com ***

For sponsorship details, email moonbuildingmag@gmail.com

***ADVERTISE HERE***

Email moonbuildingmag@gmail.com

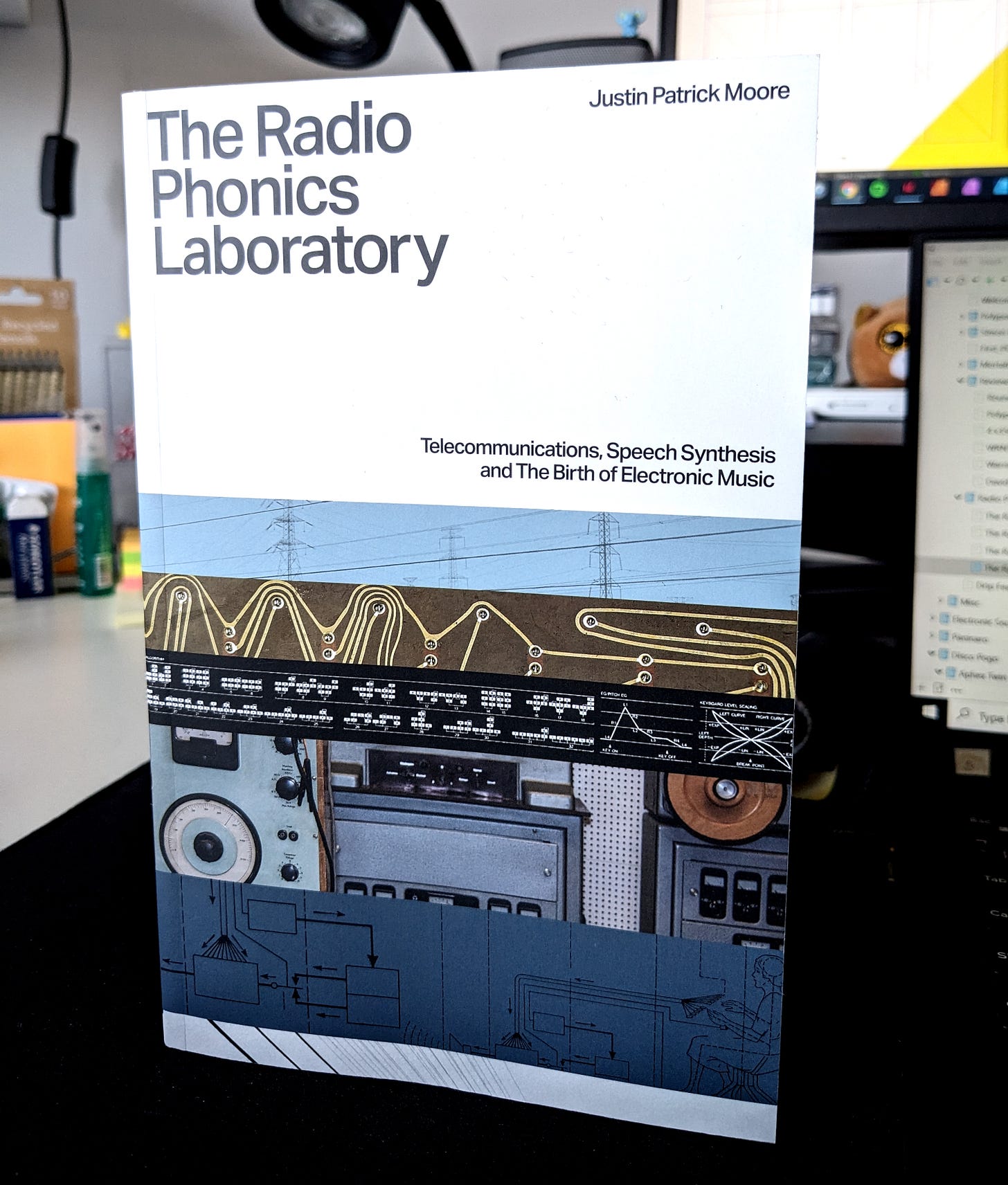

‘The Radio Phonics Laboratory – Telecommunications, Speech Synthesis And The Birth of Electronic Music’ Justin Patrick Moore (Velocity Press)

The Moonbuilding Album and Book Of The Week pieces usually come with a review followed by an interview with the artist or author. The two tend to go hand-in-hand. But the interview that follows with Justin Patrick Moore, the author of ‘The Radio Phonics Laboratory – Telecommunications, Speech Synthesis And The Birth of Electronic Music’ (Velocity Press), didn’t feel like it needed to be preceded by a review such is its comprehensive nature.

The whole story, from Justin’s beginnings in radio, making his own music, being a music writer and his love of ham radio, right through to an in-depth chat about his fine debut publication, is here. It’s a conversation that flows so nicely from beginning to end I figured I’d just run the whole thing for your reading pleasure.

What’s remarkable about the book is that the premise, that the history of electronic music is inseparable from the history of radio and telecommunications, is not one I’ve heard before. Justin argues the case brilliantly. What really staggered me was people like Daphne Oram, who we think of as the most pioneering of pioneers, were actually late to the party. It’s like that thing where you imagine Earth is 24 hours old – the dinosaur arrive at 22.56, humans at two minutes to midnight. Chapter 10 of 13 is where Daphne’s New Atlantis arrives in this story.

Needless to say, such an original idea that is presented so brilliantly really is a must-read. Without further ado I’ll hand you over to Justin…

Hello Justin, how’s things?

“Things are going well. My family are healthy, my wife has finished up her last week at the school where she works, and summer is here! I’m looking forward to some days off from my job at the library, some time to write, play radio, and escape the encroaching Ohio heat by going lake swimming in Kentucky or Indiana.”

Let’s talk about you before we get to the book. You began your radio career on a pirate station in Ohio in 1999. Were the US pirate stations much like the UK pirates?

“From what I have learned in exploring radio history, not really. US pirates tended to be a bit more freeform on the one hand or thematic on the other. They are often very iconoclastic and reflect individual visions of what radio could be.

“A case in point is the enigmatic work of Alan Maxwell. He called his project KIPM, the last three letters standing for Illuminati Prima Materia. Each of his broadcasts was like stepping into a surrealistic painting made for radio. Other pirates in the US get on the air to provide information to their ethnic communities, which have little representation on the official parts of the spectrum, but that is mostly in places like Miami and New York City as documented by David Goren.

“Others have various political agendas, and some do it in the spirit of the prank, as a form of culture jamming. From what I know of the UK scene it seems to have been to play the rock music that the BBC wouldn’t touch when Radio Caroline started. The same seems to be true as it turned into another aspect of rave culture when the BBC wouldn’t touch techno.”

Why do you think radio remains such a popular medium? As a technology it’s over 100 years old…

“Even now, if you get someone who has never been involved in radio to talk on a microphone, and someone hundreds of miles away talks back, like in ham radio, the experience is magical. Intercepting signals from around the globe on this technology still excites my mind. It does seem that with all the other tech at our disposal some of the wonder is gone, but for me whenever I tune in to a distant station that wonder returns.”

There’s always new people discovering the joys of radio too aren’t there?

“When I was a teenager community radio was a lifeline to alternative culture not heard on the corporate airwaves. The development of Software Defined Radios, coupled with computers, seems to have got a number of hacker type kids from the young generations turned on to what is going on in the aether.”

You’ve broadcast on Cincinnati’s WAIF Radio community station for a long time, how all did that begin for you?

“I was a fan of ‘Art Damage’ in high school before I ever got the chance to be on the show itself. It was started by a guy named Uncle Dave Lewis and was something of a locus for all the weird music freaks in the city. I listened as often as I could since I first discovered it, and the show turned me on to all manner of experimental sounds that I’ve maintained an interest in ever since. It was one of the first places I heard collage music and tape cut-ups. I really got into that, and around the same time got turned on to the music of Negativland. All this convinced me that, like the punks with three chords and the will to make music, I could make cut-ups in my bedroom using two tape decks and sounds I recorded off the radio.

“When I started working at the library, I met some people who were involved in the local noise/experimental/improvised music scene that was closely tied to ‘Art Damage’. My friend Jeremy Lesniak had been asked to step in as one of the rotating co-hosts, but he didn’t want to so he offered it to me and I stepped into that role in his place. Ron Orovitz had taken over as the main host, he makes noise music under the name Iovae and is really into using sine wave generators and shortwave radio, among other sources, for much of his music. He had a bevy of music makers doing the show, including violinist C Spencer Yeh/Burning Star Core. We’d each take one week out of the month, putting on lots of shows and bringing in musicians from out of town. It was an exciting time there in the early 00s.

“Later on, I got the opportunity to be part of the rotation for the more eclectic ‘On The Way To The Peak Of Normal’. When the show’s founder Craig Kelly stepped down, I took it over for a few years. That show ranged from indie and krautrock to electronica, and anything else we might want to play, leaning towards underground sounds. Craig used the Holger Czukay song the show took its name from as his opening theme, but I took to using Joe Meek’s ‘I Hear A New World’.

“Then, in 2014, I decided to call it a day at WAIF. Along with the pressure to come up with fresh two-hour mixes of music each week, it got to be a lot between the late nights in the studio and the early mornings at work the next day. I also wanted to give greater attention to my writing. I’d written, and continue to write, fiction and poetry since I was a kid, and wanted to put more effort into that. But even now I am still back at WAIF at least a couple times a year as a fill in for my friend Ken Katkin on his underground music show ‘Trash Flow Radio’. It’s great to be able to go in there and still do shows without the pressure of having to do it every week.”

Tell me about your writing adventure. You started writing about music for brainwashed.com’s The Brain? That was an interesting site, right?

“I started to write for The Brain in 2008. I remember it clearly because that was when my mom died, and it was just after I’d been in touch with Jon Whitney, who runs the site, about a CD compilation he’d made called ‘Peace For Mom’. That was in tribute to his mom who’d just passed away, and my mom died unexpectedly right after that. It was a shocking and touching synchronicity for me. I was grateful that Jon gave me the opportunity to write for The Brain and gave me something good to focus on in the aftermath of my mom’s passing.”

What did writing about music do for you?

“I’d always felt torn between writing, doing radio, and making music, so learning how to write music reviews gave me a start in bridging those worlds. The Brain was one of my go-to sites for reading about bands like Coil, Current 93, Nurse With Wound, and The Legendary Pink Dots who all remain favorites of mine. I learned a ton from reading it and writing for them. These days I’m penning some music reviews for Igloo Magazine. The site is run by Pietro Da Sacco and he has been great to collaborate with.”

And then, in 2015, you became a ham radio operator, which is a bit of a change from radio DJ. What prompted that?

“I’d always liked shortwave listening and was prompted to get into the related area of ham radio through experimental music. Stockhausen had used shortwave in his various ‘Kurzwellen’ pieces, and I really enjoy William Basinki’s ambient tape loop masterpiece ‘The River’, which was made using sounds from shortwave. Also, I’ve always loved alternative communication mediums, from the zines I read as snot-nosed teenage skater punk to the BBS’s of the early internet. I wanted to learn the technical side of radio, as well as have access to this part of the spectrum and be able to use it for communication. I also found that I’d after I’d left the station I missed radio so I decided on getting my ham license after about a year break where I was able to reset my ears musically and my mind on what I wanted to do next. So in a way, I never quit radio, only changed how I was involved with it.”

What’s the appeal of trawling the megahertz in these days of the internet where pretty much anyone you like is a click away? Is there an analogue nostalgia afoot like there is for vinyl?

“The idea that you can talk to people around the world with a modest investment in equipment and a simple wire thrown up in a tree or in an attic used as an antenna is very appealing. There is also the decentralised aspect of it. You don’t have to be connected to an internet, or even the external power grid, if you have batteries or a generator. This makes radio more resilient, in terms of natural or man-made disasters, which there seem to be more and more of these days. Point to point contacts can be made over long distances without being connected to any kind of top-down network, and to me there is a freedom in that.”

One thing leads to another here doesn’t it?

“From friends I made in the ham and shortwave community I ended up being a part of shortwave music show called ‘Imaginary Stations’ run by DJ Frederick. I was introduced to him by One Deck Pete and I produce a 15-minute segment for these shows about twice a month give or take. It’s on the fringe, but there is freedom on the fringe.”

Stupid question perhaps, but what led you to write ‘The Radio Phonics Laboratory’?

“When I started going to ham radio club meetings and studying the science and technology behind radio, I started seeing a lot of parallels to things, and how electronic music was tied into the beginnings of telegraphy and the telephone system. I had long been fascinated with the subculture of phone phreaks, and had tried to be one myself in the 90s with little success, so it was a natural direction to go. All the early electronic music studios were tied either to a radio station or to a company like RCA. A lot of the music was avant-garde or experimental, and I have a pretty strong taste for that, so I just started following my obsessions.”

Can you set the book up for us. What’s it about?

“The book is split into three sections. ‘Telemusik’, ‘The Voice Of The Bell’, and ‘We Also Have Sound Houses’. The first part deals with very early electronic instruments like telephone pioneer Elisha Gray’s simple oscillator instrument he made that was played over the telegraph wires, and Thaddeus Cahill’s massive instrument The Telharmonium, which was designed for transmission over the telephone system in 1897. This section also includes the actress and inventor Heddy Lamarr’s collaboration with composer George Antheil in developing the principal of spread spectrum radio, which is now used in WiFi.

“The second part deals specifically with the history of vocoding and speech research taking place mainly at Bell Laboratories where they were looking for ways to compress the voice to fit more calls over the phone lines. On the one hand this led to the vocoder as it is known in music, though that hadn’t been its original purpose. Its first real use was for cryptography in World War II. And the third part looks at a number of the early electronic music studios and explores the connections they had to radio stations. Along the way we meet a lot of colorful characters.”

The central idea is that the history of electronic music is inseparable from the history of radio and telecommunications. At the heart of all this is the evolution of speech synthesis. Can you explain what that is and why it’s so important?

“Speech synthesis is basically the artificial reproduction of the human ability to speak using machines. People have been trying to create artificial means of speaking for quite some time, with early attempts going back over a thousand years by medieval philosophers. Closer to our time, and what I talk about in the book, is the work of Homer Dudley who invented the vocoder, and others who followed in his footsteps. Vocoders are actually used all the time whenever people make cell phone calls, or get on Skype, Zoom or Google Meet to talk to people over computers. By breaking down the original vocals as spoken and building them back up on the other end of the line, a lot bandwidth is saved for phone and internet companies. Yet these same applications for communication were looked at creatively by composers who saw in them potential for new tonalities and sounds.”

It’s always an interesting book that only starts talking about Daphne Oram in Chapter 10! There’s a lot went on BD, before Daphne, right?

“Right! My book really only goes up to the early 1980s, with just a splash of music from the 1990s at the very end, but I was more interested in the 1880s and 1890s in many ways. Our communications systems are huge, but fragile because they are so complex. I wondered what kind of music might be made if our ability to use computers was somehow compromised. So I went back to the very beginning to see what might be possible with more limited technology. Also interesting to me was the fact that the basics of our technology haven’t really changed much except in size and efficiency since the 1950s or early 60s. First radio, then telephone, and finally digital computers have formed the basis for our global communications system. Now those three suites of technology are all just combined in different variations and arrangements, most notable in the cell phone. There is of course new software and applications, but the suite of radio, telephone and computer are the core. Beyond that it was my real love of the 20th century avant-garde that had me exploring all the stuff BD.”

There’s so much here I didn’t know. Is there anything you discovered that raised your eyebrows?

“One of the parts that really fascinated me was the section on Linear Predictive Coding, which is a form of vocoding that was independently developed in two different places at around the same time. Japanese scientist Fumitada Itakura discovered it on his own in 1966 using statistics to analyse speech and then reassemble it electronically. Just a bit later it was discovered again, though approached from a different path, by Manfred Schroeder and Bishnu Atal at Bell Labs. Then at Princeton University, the engineer Kenneth Stieglitz was helping computer music pioneer Godfrey Winham with the technical side of things and they thought Linear Predictive Coding might have applications for music. Sadly, Winham passed away, but composer Paul Lansky took up the mantle and used this tool as part of the palette for his mind-expanding electronic pieces.”

You start the book with the famous “We also have sound-houses” quote from Francis Bacon’s ‘New Atlantis’. Why has something written in the 15th century resonated through the ages so much?

“I think it’s because it shows how people have been on this quest for knowledge and wisdom about sound for centuries. Certain ideas, like certain sounds, resonate and resound for long periods of time. Then someone like Daphne Oram will come along and remind us of these connections to the past, striking the note again so that it may be sustained for another length of time to come.”

That quote was hung on the wall at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, how were they specifically shaped by telecoms?

“The Royal Society was shaped by Bacon’s writings, and when Oram hung that phrase on the wall at The Workshop I think it was her way of saying that the work they were doing was valid scientific and aesthetic research into the nature of sound itself. The Workshop did mostly incidental music, but I don’t think it would have come into existence if there weren’t radio dramas and television shows in need of their kind of special sound. But it took visionaries to convince the higher ups to make it happen.”

Do you think it’s possible to rank the influence of the European sound studios?

“It’s possible, but it would be difficult! I mean, it’s hard to underrate the importance of the original two kinds of schools of electronic music that developed out of Pierre Schaeffer’s GRMC, and the Electronic Music Studio at the WDR where Karlheinz Stockhausen became the director. They each had their own specific style and approach, equally valid, but that would eventually be combined by others.”

OK, but do you have a favourite sound studio?

“Call me biased, but I am rather partial to the music made at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in America. I was obsessed with a record they put out of works recorded between 1961 and 1973 in my early 20s. It had a piece on it, ‘Out Of Into’ by Bülent Arel and Daria Semegen that got me excited about this whole era and area of music.”

Do all those sound studios pale into insignificance when you consider that without the telecommunications pioneers none of it would have been possible?

“They certainly made the cornerstone out of which these laboratories could be built. And I think in that era, when electronic music was new, there weren’t any or many examples of what already been done to fall back onto so they had to use their imaginations to really see where they wanted to go. To do it, they used tools like radio test and calibration equipment that hadn’t been built for musicians. Now people have access to all kinds of tools, ready to go. I think the challenge for composers today is to break out of the built-in presets and perhaps be able to begin using these tools in ways they hadn’t been intended to be used for in the first place.”

The advent of FM synthesis for music is pretty key isn’t it?

“Yes, and I wanted to dig into it because the same principles that makes frequency modulation possible with radio waves, giving us FM radio, is also what is at work with FM synthesis via audio waves. But it took someone like John Chowning who investigated sound with the mindset of a hacker to realise frequency modulation could be done with audio waves.”

And the Yamaha DX7 is quite important. Not least because it was hard to use so musicians used the same sounds a lot! What was the impact of that do you think?

“Ha-ha, that’s funny. I don’t know, you’d have to ask Eno about that, he did seem to take the time to dig in deeper to the DX7 and see what it could do. I think the plug and play culture has its limitations especially if we don’t ever open the hood and see what is going on underneath it all. Thinking of how long classical musicians train, in Western music and in north Indian classical music, gives me another level of respect for people who commit to music as a way of life. It took John Chowning a long time to do the work necessary to achieve FM synthesis, yet if you just go to the presets and not really explore it, you might not find much that sounds new. But there is also something to be said about just getting to work quickly with whatever is at hand…”

Reading about the early innovations in all this is fascinating - you don’t seem to travel much beyond the 1980s, how come?

“Maybe because of all those presets being used on the DX7… no, I just had to cut it off somewhere, and the time around the establishment of IRCAM seemed a likely place. There are of course other ‘sound-houses’ I didn’t cover or include, some coming later, others already established, that I didn’t have room for.”

Where does all this ultimately lead? AI is already involved, isn’t? What are the implications of that and what’s next?

“If you look on YouTube or Bandcamp you can find some strange material using AI-generated voices and songs. A lot of it is really juvenile potty humour and worse, good for a laugh maybe, depending on your tolerance for such things. A user by the name of Obscurest Vinyl has been making songs that might fool some listeners to thinking they came from anywhere between the 50s through 70s or so, except for the profane lyrics, so when you listen you know the voices and music were all generated using AI. It will be interesting to see what someone who has something other than potty humor to offer might do with these tools, though I’m not at all opposed to humour in music. I think we need more of that actually. I mean, you can’t just listen to Stockhausen all the time.”

And what’s next for you? Any more books up your sleeve?

“I hope so. When I started on this project I wrote quite a bit of material, and then realised I had too much to fit into one book, so I chunked off one bit, and have another bit that is in a more or less finished draft state though I’d like to do some interviews with the people involved. There are more of them still around then there were for those I cover in this book.

“That material deals with the use of the radio as a musical instrument in itself by people who sample shortwave or use it live. It’s also about radio astronomy and people who made or make music based on radio waves from outer space, a contemporary music of the spheres. Another aspect is the DIY electronics factor as well as the idea of transmission arts, people playing their music on the radio in unique ways, such as the long-running program associated with Negativland, ‘Over The Edge’ on KPFA.

“I also have some material for a third book, on information theory and sonification that I am working on now. If I am lucky, and other people are as interested in my obsessions as I am, I will get to share this material with readers as well.”

‘The Radio Phonics Laboratory’ is published by Velocity Press and is out now. An edited version of this interview appears in the new issue Moonbuilding

***ADVERTISE HERE***

Email moonbuildingmag@gmail.com

A MESSAGE FROM THE MOTHERSHIP

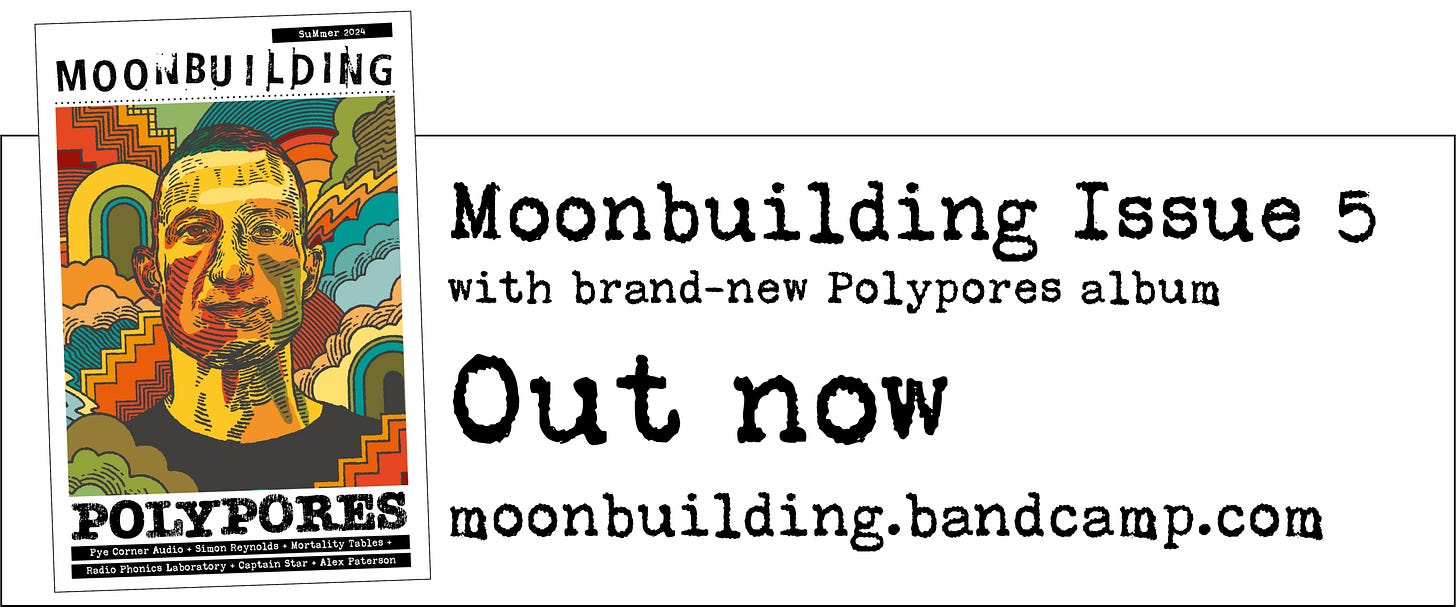

***THE NEW ISSUE OF MOONBUILDING IS OUT NOW***

Bloody hell! Will you look at that? The new issue of MOONBUILDING, Issue 5 for those of you who are counting, is here. Yes, we’ve taken our sweet time, but it is very much worth the wait.

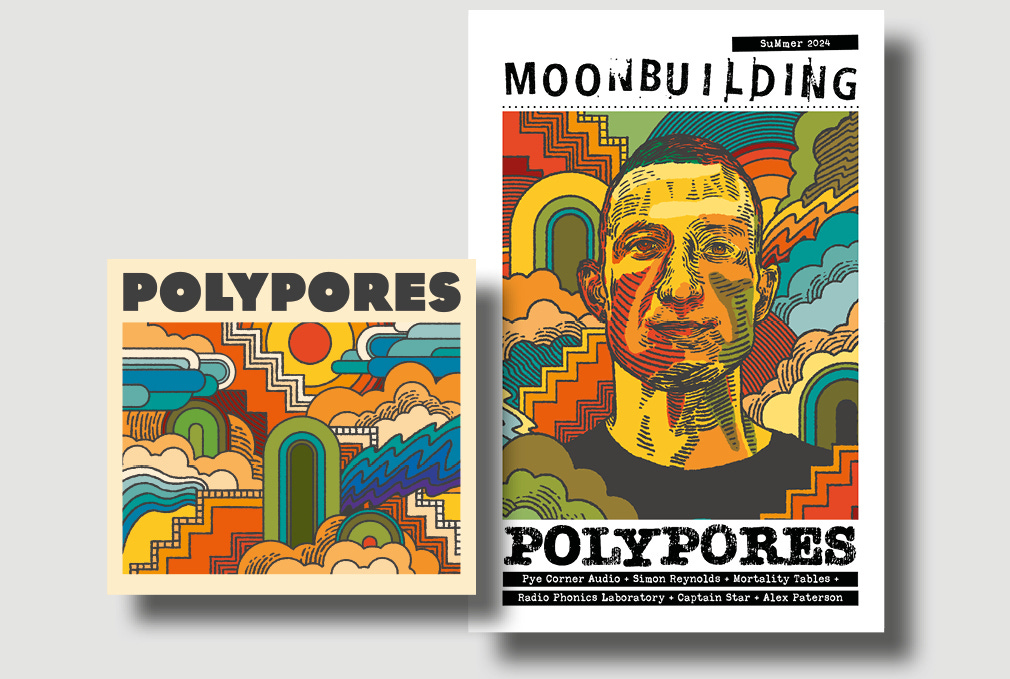

On the cover, with another cracking illustration from the untouchable Nick Taylor, is the awesome Polypores. In our free-wheeling chat we get right under the hood of Stephen James Buckley’s musical operation, offer up a listening guide to help you safely navigate his extensive back catalogue and we also have an whole new Polypores album exclusively for you.

Yes, you read that right. We are giving you a freshly minted, not available anywhere else new album called ‘The Album I Would Have Released In An Alternate Universe’, which happens to be the sister recording to his forthcoming Castles In Space album ‘There Are Other Worlds’. Read all about it in the new issue where Stephen talks you though it track by track.

If you’d like an extract from our Polypores cover feature interview where Stephen Buckley talks about his formative influences, which probably aren’t what you’d image, you can do that here… moonbuilding.substack.com/p/issue-28a-26-july-2024

Elsewhere in the new issue, there’s a profile of our new favourite label Mortality Tables, Pye Corner Audio gets in on the There’s A First Time For Everything act, we round up an absolute mountain of recent releases and serve up our thoughts on the best albums from the last few months, including Loula Yorke and Warrington-Runcorn New Town Development Plan. There’s a column from The Orb’s Alex Paterson, which starts off about Jah Wobble and ends up about Andrew Weatherall, and an all-new instalment of the brilliant Captain Star cartoon strip.

We’ve gone book crazy of late and this issue features a shit-tonne of great book reviews (that’s great books, reviewed, rather than the reviews being great, although they are pretty good). There’s a cracking chat with Justin Patrick Moore, the author of ‘The Radio Phonic Laboratory’, and a bonus chinwag with the world’s finest music journalist, Mr Simon Reynolds.

You will be kicking yourself and quite hard if you miss out on this issue. The virtual shop doors are open now at moonbuilding.bandcamp.com for your purchasing pleasure. Don’t delay, this magazine ain’t going to buy itself. Call it scarcity marketing if you like, but snooze and you lose.

Moonbuilding Weekly is a Castles In Space publication.

Copyright © 2024 Moonbuilding